Look Back to Move Forward

In the 1980s, the outbreak of AIDS swept the country. Claiming thousands of lives, it quickly became a humanitarian crisis that cried out for help. But, tragically, help wasn’t easy to come by. Since it was seen as predominantly affecting homosexual men and injection drug users, sufferers faced wide-spread discrimination. Even as the virus became the leading cause of death, the US government’s decade-long response went from evasion to lip service.

For one thing, lawmakers didn’t want you to be gay. It was ungodlike, a “crime against nature” that was legally punishable in many states. Just think about it: Homosexuality between consenting adults was prohibited by the government. The dark hearted and narrow minded believed it was a choice, a choice with consequences. Some advocated forced ‘‘conversion therapy” or other measures to rid you of the demons. But even legislators without bias, on the more humanistic end of the spectrum, turned a blind eye for fear their constituents wouldn’t understand.

Making matters worse, and another casualty of stigma, mass media did not address the facts, and misinformation ran rampant. Ignorance of the ways in which the HIV virus was, and was not, transmitted promoted irrational fears that gave way to hate. The ensuing hysteria and panic exacerbated the misery—people were evicted, schools barred children, and even doctors steered clear, denying medical care. Those who were infected didn’t just fight against overwhelming odds to live, but they were shunned or worse—with all-too-common violent backlash from the community. Ignorance prevailed and people died at alarming rates, with annual fatalities going from 13,000 in 1987 to nearly 42,000 by 1996.

Fueled by the inactivity of the federal government, AIDS activists took the lead, promoting awareness of the disease and simultaneously pushing for research, education, and access to services—providing condoms and clean needle programs—to reduce harm. A formidable force, and increasingly mobilized with scientific evidence, activism eventually made headway.

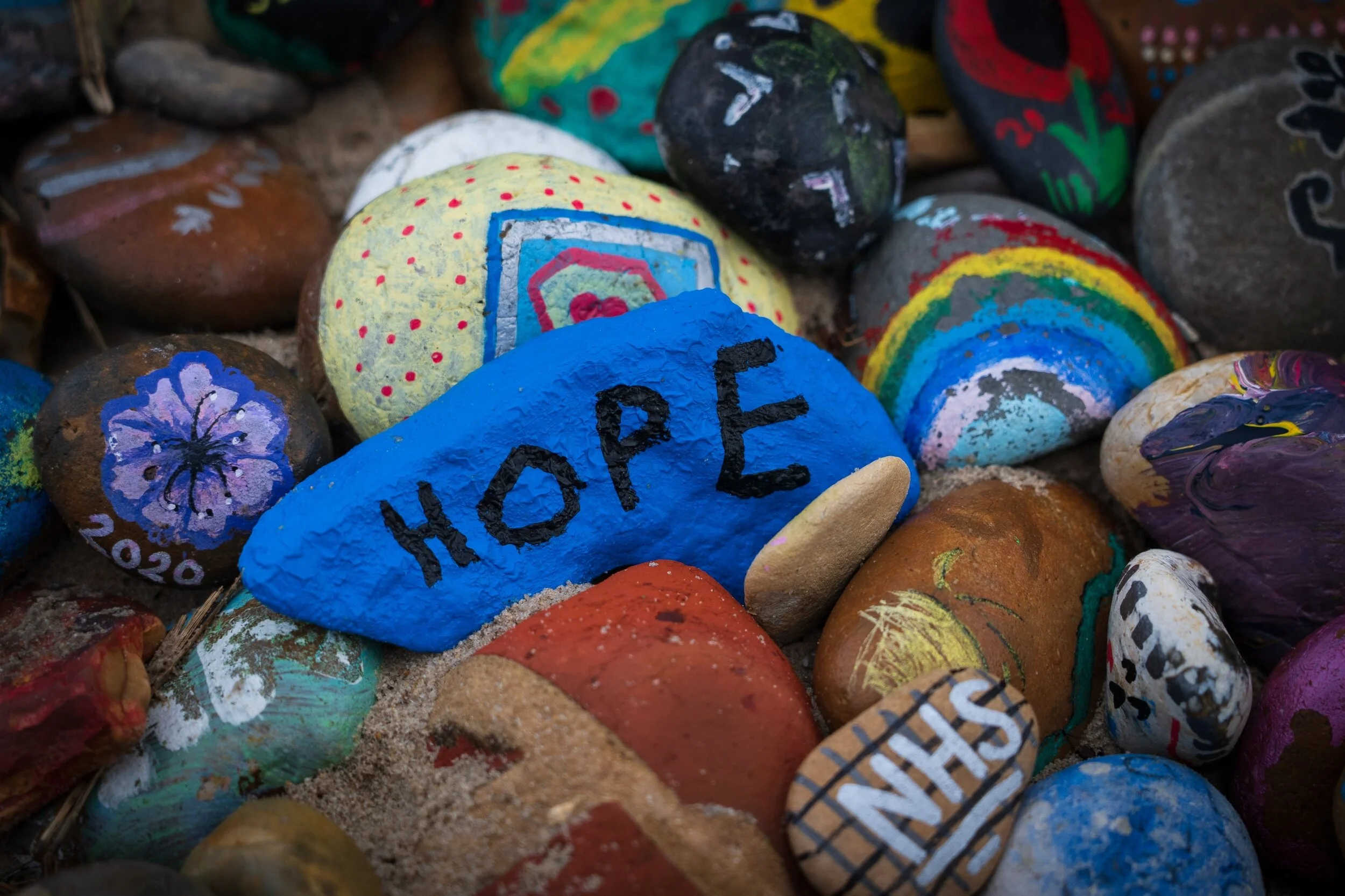

Funding allocations enabled a breakthrough in multidrug therapy and, by 2000, the number of deaths began to decline. Advances in care have provided hope for people living with AIDS and for those at risk for HIV. Thankfully, we also have evolved as a society, shedding the need to prohibit individual behavior, to legislate sexual preference. Even so, there is more to be done to combat HIV/AIDS. Continued research in the development of a vaccine is a priority as is addressing the pattern of inequity in prevention services among various jurisdictions along with the disproportionate impact of the virus on marginalized communities.

I cannot help but draw comparisons to the current overdose epidemic:

It is a humanitarian crisis that cries out for help.

Government control, i.e. prohibition, does not save lives.

Those who suffer face discrimination and inhumane circumstances.

The mindset of conversion therapy is akin to coerced treatment.

Punishment eclipses health care.

Criminalizing the afflicted fans the flames of stigma.

Lawmakers avoid reform due to public perception based on stigma.

The media relentlessly perpetuates the myths.

Misinformation runs rampant.

Activists and scientists fight to promote factual information.

Preventative and risk-reduction services are limited by legal resistance.

Communities of color and low income pay the steepest price.

I realize there are differences between these two deadly epidemics, one of which is that the number of annual drug overdose deaths is double that of the peak year of the AIDS crisis. Other ways they diverge may be obvious. But the commonalities are as profound as they are heart-wrenching: 1) Human suffering is met with cruel treatment and indifference among those who could affect change, 2) Myths and misunderstandings fuel stigma and derail needed interventions, 3) Prohibition rules but is not, and never has been, a strategy for saving lives, and 4) Health care and humanity will save the day as soon as we come to our senses and stop vilifying people whose choices do not violate the rights of others.

I believe these striking similarities are worth consideration as we fight to turn the corner on the still-rising number of preventable overdose deaths. If we think COVID-19 is the sole reason for 2020’s increase in overdose deaths, how do we explain the increase from 2018 to 2019—before the pandemic hit?

[photo credit: Nick Fewings]